About the Work

Since the 1970s Jyoti Duwadi has created a multifaceted body of work. His sculptures, paintings, drawings, installations, and digital art reflect an openness to both chance and discovery.

Jyoti experiments with a wide and remarkable array of natural materials and human-made objects, including industrial sanding belts, bamboo, beeswax, and earth gathered from around the world. The artist displays an innate ability to transform ordinary, discarded objects, such as the humble egg carton, into sculptures.

Often the results are humorous, as in his series of waxed sculptures – an old travel iron, repaired tea pot, antique automobile gas funnel – that can be appreciated for their relationship to Pop Art. Jyoti diverges from this 1960s movement by accentuating an object’s formal design and creating sensuous surfaces.

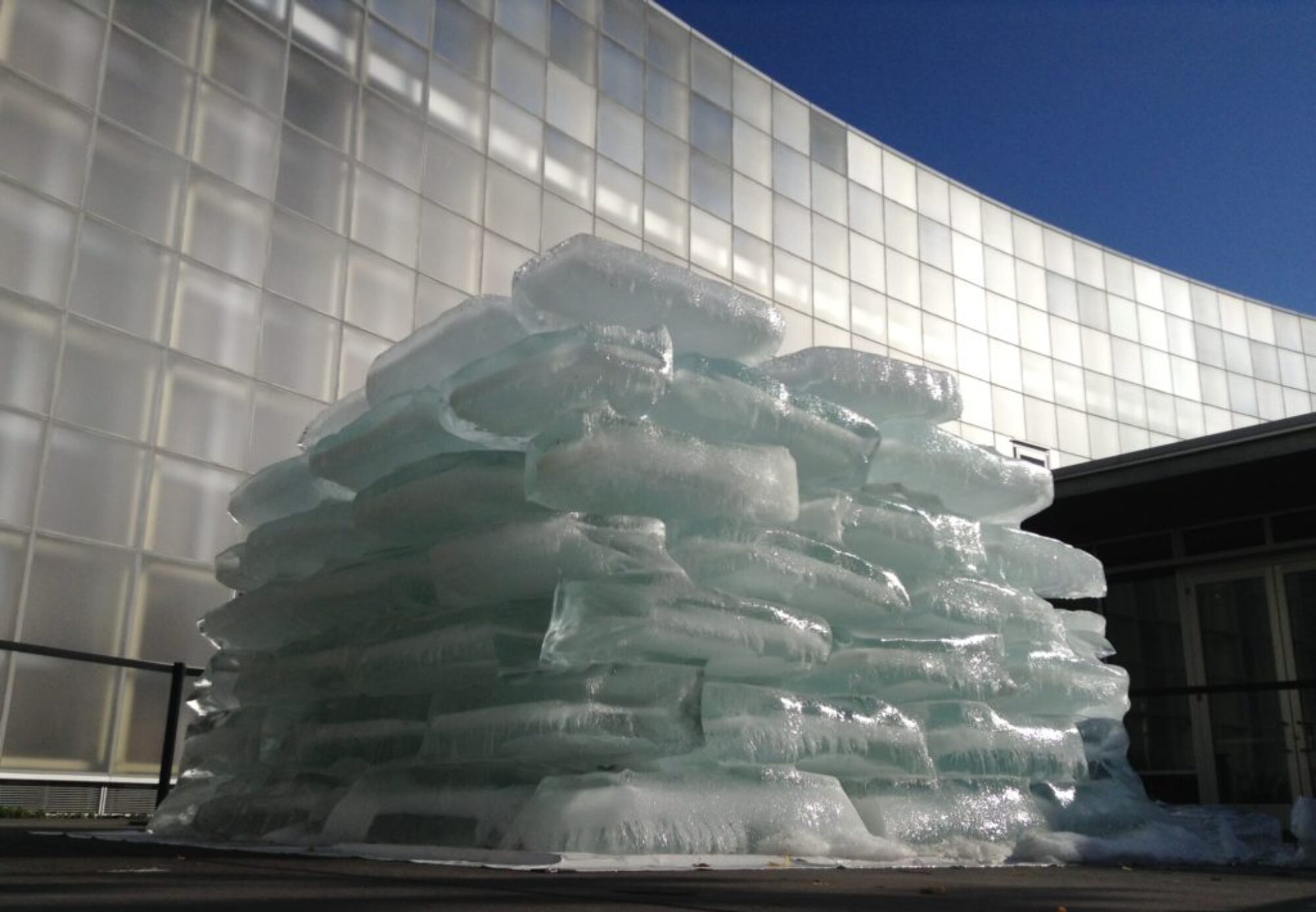

Many of Jyoti’s artworks, made from natural elements that express the intrinsic beauty of Earth’s forms and colors, are intimately scaled for personal reflection. By contrast, his views about war and peace, climate change, and the loss of biodiversity take the form of large-scale sculptural installations and remediation projects involving community participation.